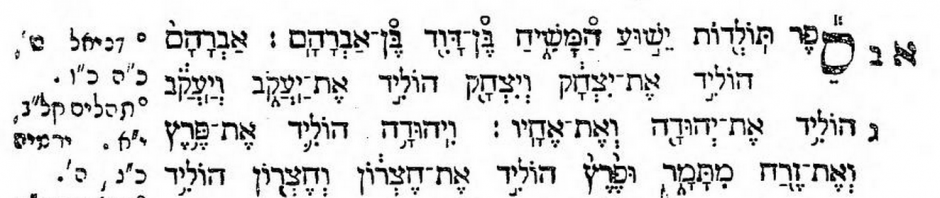

Picture of the Holy Child of La Guardia in annual procession every September 27 in the town of Toledo.

“For centuries there had been tales that during Holy Week the Jews crucified a Christian child in the same way that they had crucified Christ. This time it was believed – not by the inquisitors, whom it was difficult to deceive, but by the people. The story of the Holy Child of La Guardia was the pretext with which those who were demanding the expulsion of the Jews extorted the consent of Isabel:”, Pierre Chaunu, 1492. L’année de L’Espagne, L’Histoire

In June 1490, a roving carder, a converso named Benito Garcia, aged 60, a native of the town of La Guardia, was stopped in Astorga in the province of León. [From “The Jew As Witch: Displaced Aggression and the Myth of the Santo Niño de La Guardia” by Stephen Haliczer]

A consecrated Host [communion wafer] was discovered in his knapsack. He was taken for interrogation before the Vicar-general (Judicial Judge) of the Bishopric of Astorga, Pedro de Villada. The confession of Benito Garcia, dated June 6, 1490 has survived and indicates that he was only accused of Judaizing. The defendant explained that five years earlier (1485) he had secretly returned to the Jewish faith, encouraged by another converso, Juan de Ocaña, who was also from La Guardia and a Jew from the nearby locality of Tembleque, named Franco.

Furthermore, the plotters were alleged to have gone to great lengths in order to imitate Christ’s Passion down to the smallest detail. On 24 September 1491, Benito García, one of the hapless conversos, was accused of having carried the child to a cave near La Guardia where he had been nailed to a wooden cross, lashed repeatedly, and a crown of thorns placed on his head.[20] While the child was being beaten, his supposed torturers recited curses designed to mock Christ for whom the child was a substitute. Among other things, Christ was called a “traitor and deceiver who had preached lies against the Jewish faith,” an “evil sorcerer who had sought to destroy the Jews and Judaism,” and the “bastard son of a perverse and adulterous woman.”[21] In this way, out of the pain and torment inflicted on their Jewish and converso victims, Avila’s special inquisitors had managed to concoct an extraordinarily suggestive myth which lent itself easily to being further elaborated and made more horrifying by later authors.

The Holy Child of La Guardia (Spanish: El Santo Niño de La Guardia) (died 1491) was, at first, believed to be the victim of a ritual murder by Jews in the town of La Guardia in the central Spanish province of Toledo (Castile–La Mancha). On November 16, 1491 an auto-da-fé held outside of Ávila concluded the case with the public execution of several Jewish and converso suspects who confessed to the crime under torture. Among the executed were Benito Garcia, the converso who initially confessed to the murder. However, no body was ever found, and because of contradictory confessions, the court had trouble coherently depicting how events took place.

Like Pedro de Arbués, the Holy Infant was quickly made into a saint by popular acclaim, and his death greatly assisted the Spanish Inquisition and its Inquisitor General, Tomás de Torquemada, in their campaign against heresy and crypto-Judaism. The cult of the Holy Infant is still celebrated in La Guardia.

The alleged murder by Jews has been called “one of the most notable and disastrous lies of history”, as quoted in the Catholic Encyclopedia.

Reflection and Prayer: We have recorded several instances of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe, such as that of Hugh of Lincoln, Simon of Trent, and others. On this day in La Guardia, Spain, on the eve of the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, another gross libel is spread. As has been pointed out, the Jews are made responsible for the guilt and fears of the Christians, and their ‘crimes’ are a projection without basis, fair trial or Christian love.

Father, forgive your church for spreading slander and lies against your people Israel, and especially those ‘conversos’ caught in between the hostility and misunderstanding between the two communities. In Yeshua’s name we pray. Amen.

http://www.materialesdehistoria.org/guardia_english.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_Child_of_La_Guardia

http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft396nb1w0&chunk.id=d0e6257

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0012_0_11763.html

Stephen Haliczer, “The Jew As Witch: Displaced Aggression and the Myth of the Santo Niño de La Guardia” in The Impact of the Inquisition in Spain and the New World. Edited by Mary Elizabeth Perry and Anne J. Cruz, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, 1991.

LA GUARDIA, HOLY CHILD OF, subject of a *blood libel who became revered as a saint by the Spanish populace. Six Conversos and two Jews, inhabitants of La Guardia, Tembleque, and Zamora, were tried in connection with this libel in an irregular Inquisition trial which began on Dec. 17, 1490, and was concluded on Nov. 14, 1491, when the accused were burned at the stake in the town of Ávila. The Jews accused were Yuce Franco of Tembleque and Moses Abenamias of Zamora; the Conversos were Alonso, Juan, García, and Lope, all of the Franco family, and Juan de Oraña, all inhabitants of La Guardia, in the province of Toledo. The depositions and confessions extracted under torture reveal that they were accused of two things: the profanation of a Host, which the accused Conversos had purchased and which was found in the bag of Benito García, in order to perform acts of sorcery; and the murder of a Christian child (whose body was never found) on Good Friday and the extraction of his heart for acts of sorcery. The beginnings of the trial have never been clarified, but during the proceedings its motivations became evident. *Torquemada himself had intended to preside over the trial, but possibly under the influence of Abraham *Seneor, whom they at first attempted to involve in the accusation, the trial was transferred from Segovia, where it was to have been held initially, to Ávila.

A special tribunal was thus set up, formed by carefully chosen judges. The judges and the investigators who assisted them resorted to provocatory methods to extract evidence in prison and were even compelled, in order to reconcile the contradictions between the various “statements,” to bring together the accused and force them to relate in each other’s presence details of the “deed” so that a tale of at least some coherence could be contrived. The judges even sat on a special panel (Consulta-de-fé) in Salamanca, with the participation of the celebrated monk Antonio de la Peña, the associate of Fernando de Santo Domingo in his anti-Jewish activities. There is also no doubt that the Inquisition wanted to prepare public opinion for the expulsion of the Jews from Spain by creating a background of an alleged Jewish-Converso conspiracy to bring about the annihilation of both Christianity and the Inquisition. Even so, the recorded statements of the Conversos are a profound expression of their belief in the Law of Moses, their readiness to die as martyrs, and their contemptuous attitude toward Christianity and its way of life. Torquemada was referred to by one of the accused as the “arch antichrist” (antecristo mayor).

The verdict was made public and circulated throughout Spain, and the worship of the “Holy Child” was rapidly instituted. For fear of riots, the Jews of Ávila felt compelled to request a document of protection (granted on Dec. 9, 1491). With time, details were added to the story until it assumed impressive proportions in works and plays which were presented on the subject. In 1583 Fray Rodrigo de Yepes wrote a book entitled Historia de la muerte y glorioso martirio del Sancto Inocente, que llaman de La Guardia, which during the 17th century served as the basis of a play by Lope de Vega, El Niño Inocente de la Guardia. Lope’s play is based on a text in his work Octava parte (1617) which is not entirely reliable. The intention of Lope is purely anti-Jewish. The martyrdom of the Santo Niño is compared to the Passion. Lope leaves no doubt as to his sympathy with the Inquisition and his dislike of those it prosecuted. The tale was newly adapted during the 18th century by Jose de Cañizares under the title La Viva Imagen de Cristo. These works were republished in 1943, during World War II, by Manuel Romero de Castilla under the title Singular suceso en el reinado de los Reyes Católicos, in an attempt to revive the “holy” ideas of the writings of his predecessors.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Fita, in: Boletín de la Academia de la Historia, Madrid, 11 (1887), 3–134, 420–3; H.C. Lea, Chapters from the Religious History of Spain (1890), 203ff.; idem, History of the Inquisition in Spain, 1 (1904), 133–5; T. Hope, Torquemada (Eng., 1939), 153–92; Baer, Spain, 2 (1966), 398–423; Suárez Fernández, Documentos, 44. ADD. BIBLIOGRAPHY: Ph. Brunet, Torquemada et les atrocités de l’Inquisition (1976), 199–215; C. Carrete Parrondo, in: Helmantica, 28 (1977), 51–61; Sor. M. Despina, in: El Olivo, 9 (1979), 48–70; W.A. Christian, Local Religion in Sixteenth century Spain (1981), index; S. de Horozco, Relaciones históricas toledanas, Intr. & trans. by J. Weiner (1981), 29–38; F. Díaz-Plaja (ed.), Historia de España en sus documentos, siglo XV (1984), 278–91; L. de Vega, El niño inocente de La Gurdia: A Critical and Annotated Edition, with an Introductory Study by A.J. Farrell (1985); M. Moner, in: La leyenda: antrpología, historia, literatura, (1989), 253–66; E.M. Domínguez de Paz and M.P. Carrascosa, in: Canente, 5b (1989), 25–38; idem, in: Diálogos hispánicos de Amsterdam, 8:2 (1989), 343–57; A. MacKay, in: J. Lowe and P. Swanson (eds.), Essays on Hispanic Themes in Honour of Edward C. Riley (1989), 41–50; S. Haliczer, in: Cultural Encounters (1991), 146–56.

[Haim Beinart]

Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2008 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved.

The Inquisition was nothing if not brutal and unjust. Perhaps the most infamous case was of Benito García, a converso pilgrim who was returning from Santiago de Compostela. In Astorga, during an evening drinking with some locals, he was caught with a consecrated wafer in his knapsack. After six days of torture, he confessed to murdering a Christian boy with the intention of using his heart and the wafer in a diabolical ritual. García and seven co-conspirators, named under confession, were burned at the stake for the ‘crime’.

A couple of interesting footnotes; the wafer found in the knapsack became a holy relic for a few decades afterward, and was even supposed to have kept the plague away from Avila in the following century. And, even though no body was ever found, a church was built to Christopher, ‘The Sainted Innocent’, on the spot in La Guardia where the plot was supposedly hatched.

The Trial of 1491 and the Expulsion of 1492

http://www.materialesdehistoria.org/guardia_english.htm

“All of us who were in the cave crucified the boy on a cross we made of stakes.” Confession of Yuce Franco, Avila, interrogation of 19th July 1491, afternoon.

The Inquisition functioned according to a fixed programme, which subsequent investigations and discoveries had to conform to. Arrests and sentences were the result of the lists of sins to be ferreted out, just as in any other old‑style police operations. The preliminaries of the case of the Holy Child of La Guardia are very complicated, but it seems that it all began with the disappearance of a child in Toledo during the Corpus Christi procession or that of the Assumption of the Virgin. The confusion about the start of the inquiry is so great that, though the child is said to have been baptized in the church of San Andres de Toledo, his origin was Aragonese, causing several historians to confuse La Guardia with a town of the same name in the Rioja (Alava), while some mention the one in Jaen Province and others the one in the Province of Toledo. The child was called Juan according to the earliest documents but later the more Christ‑like name of Christobal was preferred. So as not to get in a muddle, the chroniclers therefore chose to call him the Holy Child of La Guardia, a generic name for a child who may have never existed, either dead or alive.

According to confessions extracted under torture, the Holy Child was three or four years old when kidnapped at the Puerta del Perdon in Toledo, but some preferred the age of seven as marking the boundary between the age of childish innocence and that of reason.

The events had purportedly taken place in 1489 and the trial began on 17th December 1490. It was between 6th June and 19th July 1490 that Tomas de Torquemada ordered the arrest of Yuce Franco and his alleged accomplices, whose cases he intended to judge “in person or by such person or persons as are properly informed about them to whom we may entrust the hearing of the cases.” The accused persons were of varied origin, a fact that reveals the inquisitors’ desire to implicate the various ghettos and Jewish groups of Castile in a single network of conspiracy.

What could have inspired this abduction and the subsequent murder? According to the record of the trial the accused believed that, by mingling the blood of the child with a consecrated host, they could poison the wells, thus causing the death of the inquisitors. They had been recommended to do this by the Grand Rabbinate of France! All the participants were Jews and New Christians of Jewish origin fearful of justice for having “lapsed into their former religion”. Despite exhaustive search no body was ever found in the cave where the boy was supposed to have been tortured to death, and the reason most frequently given for this failure on the part of the authorities is that the Holy Child had, of course, ascended to Heaven after his martyrdom.

The detained Jews and New Christians confessed that they had taken the child to La Guardia because of the town’s similarity to the landscape of Palestine. This, though it may seem weird to us, was the principal evidence in the trial: “Since the place was geographically like, and had geologically similar surroundings to, those places in Asia that saw the birth and death of the incarnate Son of God when He made His pilgrimage to redeem humanity, the rite would there have more similarity to, and would gain more realistic force from, that great event which lives for ever in the memory of every generation and epoch.”

The similarity of this district to Judea was defended by Friar Antonio de Guzmán using maps and the irrefutable evidence provided by divine revelations granted to his saintly colleague, Simon de Roxas. To confirm the verisimilitude of the crime, were that necessary, each of the butchers played the role of one of the personages in the gospel story of the Passion (Judas, Pilate, the High Priest, etc.), while the unhappy child took the main part, Jesus Christ.

A recent historian, Luis Suarez Fernandez, tells us: “The Inquisition proceedings began on 17th December 1490 and ended on 16th November of the following year with the execution of all the accused men: two Jews ‑ Yuce Franco of Tembleque, and Moshe Abenamias of Zamora; and six New Christians ‑ Alonso, Lope, Garcia and Juan Franco, Juan Ocaña and Benito Garcia, all of them residents of La Guardia in the diocese of Toledo. The declarations of the condemned men, both under torture and when free from it, seem to show that in fact two crimes were committed at La Guardia: desecration of a consecrated host, which the New Christians bought so as to practice magic that would save them from the Inquisition, and the ritual murder of a child crucified on Good Friday.”

With an interesting mixture of ingenuousness and brutality Anton Gonzalez, notary of the town of Avila, described the execution of Benito Garcia de las Mesuras from La Guardia on 17th November 1491: “Thanks be to God, I can inform you that he died a Christian and a Catholic, and I had him strangled (at the stake before he was burnt). Juan de Ocana and Juan Franco also showed much faith and penitence. They died professing their belief in God and acknowledging their crimes, and I hope that God may have mercy on their souls. The others died as good Jews, tortured with red‑hot pincers (and burnt alive over a slow fire). They denied their cruel crimes and called neither on God nor on the Virgin Mary, not even making the sign of the Cross. Do not intercede with God for them, since their sepulchre is in Hell.”

This notary, Anton Gonzalez, who participated in the proceedings, taking down the depositions of the Franco brothers at E1 Brasero de la Dehesa, wrote also on 17th November 1491 to the magistrates of La Guardia, telling them not to allow the dogwood field at Santa Maria de Pera to be ploughed, since it was there that Juan Franco had, at the very last, indicated that the child was buried and “this is something that must be seen by Their Majesties and by the Lord Cardinal and by all the world.” But the body did not appear.

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

LikeLike

Pingback: This Day, June 6, In Jewish History by Mitchell A and Deb Levin Z"L #ourCOG – ourcog