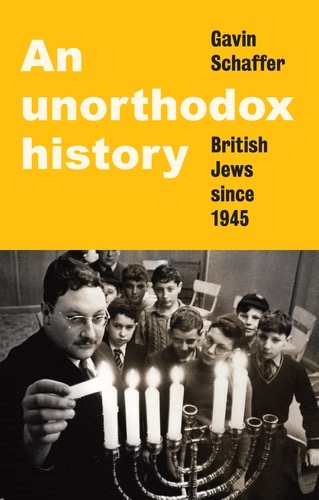

“Most controversially of all, I have given a chapter to Messianic Jews”

Gavin Schaffer is Professor of Modern British History at Manchester Metropolitan University. He is the author of numerous books and articles on race, ethnicity and immigrant history. When I met with him in 2019 we little realised that his book would not appear until 2025. After delays due to Covid it has now appeared.

Gavin Schaffer’s An Unorthodox History presents a provocative and detailed exploration of modern Jewish history in Britain, with particular attention to the role of Messianic Jews in shaping modern religious and cultural discourse. As someone who helped in his research, I approach Schaffer’s work with appreciation for its detailed historical inquiry, while offering some critical reflections on its portrayal of Messianic Jews .

Departing from traditional narratives that often focus on external perceptions of Jews, Schaffer focuses on the problematic experiences and marginalised voices within the Jewish community itself. He addresses the complexities of inclusion and exclusion, by discussing in detail those groups that have been ignored or worse within Jewish history and culture, such as queer Jews, Jews married to non-Jews, Israel-critical Jews, and especially Messianic Jews. By bringing these diverse stories together, Schaffer challenges the notion that British Jewish life is in terminal decline, instead demonstrating that Jewish Britain is thriving and deeply embedded in the country’s history and culture.

Schaffer sets the stage in the Introduction by questioning traditional narratives and emphasizing the need to focus on the internal dynamics of the British Jewish community. He gives us something of his own family’s story, setting in context the way he is doing his own work, recognising that “writing Jewish history remains a political act laden with risks and responsibilities” (p3). He is to be congratulated for stepping out and risking the ire of the community gate-keepers and official voices by venturing into uncharted territory that is often avoided or misrepresented.

Chapter 1, “The Last Jew of Merthyr and Other Bubbe Meises: Jewish History and Heritage in Flux” examines the evolving nature of Jewish history and heritage, highlighting how stories and myths shape communal identity. Schaffer connects this with his own family story, connecting the personal with the communal to avoid generalisation and tell the story with local colour and humour.

Chapter 2, “Meshuga Frum? Devotion and Division in Religious Practice” describes the spectrum of religious observance within the community, from ultra-Orthodox practices to secular approaches, and the tensions that arise from these differences. Each of us will recognise a family member that corresponds to the different types described, and also the tensions within the community that we have lived through such as the “Jacobs affair” (1961) when Louis Jacobs was not allowed to become Principle of Jews’ College because he doubted the inspiration of the Pentateuch, and the debacle over Chief Rabbi Jonatha Sachs refusing to attend the memorial service for Holocaust survivor and beloved Reform Rabbi Hugo Gryn in 1996.

In chapter 3, “We Speak for Them’: Political Activism in the Six-Day War and the Campaign for Soviet Jewry” Schaffer is on less controversial grounds, looking at British Jewry’s involvement in the 1967 war (I remember my family volunteering) and the activism that transformed the rather sleepy Jewish community into political activists in support of the refusniks. But in chapter 4, ‘These Wicked Sons’: Israel-Critical Jews and the Zionist Majority” he looks at the internal debates surrounding Zionism, focusing on those within the community who critique Israeli policies and how they are perceived by the Zionist majority. In the light of the Israel-Gaza war today this chapter provides insight and wisdom on the deep divisions within our community on these questions.

“Oi Vay – I’m Jewish and Gay: Queer Jewish Lives and the Struggle for Recognition” (chapter 5) is a clear, empathetic and deeply moving story of how LGBTQ+ Jews eventually found a grudging recognition of their existence, and then in some quarters, their acceptance. Schaffer also puts on record some of the anger, misunderstanding and distrust shown by some communal leaders towards them. I was struck by the fact that some of the leaders I most admired failed to have anything positive to say, whilst others were prepared to step out to affirm that LGBTQ+ Jews should be accepted as such.

In chapter 6, “The (Un)forgivable Sin: Intimacy, Love, and Interfaith Marriage” Schaffer examines the complexities surrounding interfaith marriages, the community’s responses, and the implications for Jewish identity. Again, a thought-provoking chapter, showing how much has changed in the community since the 1960s.

Many of us in the BMJA will be grateful for chapter 7, “The Nice Jewish Boy (Who Believes in Jesus): Jews, Christianity, and the Challenge of Messianic Judaism”, We were there, we know the people involved, and some of us were interviewed for the chapter. Schaffer tells the story with sympathy and sensitivity but also constructs the narrative primarily as adversarial. He does not conduct his own theological investigation of who Yeshua is or whether you can be Jewish and be a disciple of his. Rather he tells the unfolding story of the rise of Messianic Judaism in the UK and the arrival of Jews for Jesus in the 1980s, Archbishop George Carey’s renunciation of the patronage of the Church’s Ministry among Jewish People (CMJ) in 1992, the involvement of the Council of Christians and Jews (CCJ), the story of Helen Shapiro and comments from others interviewed. The tragic misfortune of Benjamin Lesser’s suicide and the angry diatribes of the anti-missionary organisation “Operation Judaism” are recounted, showing how they viewed Messianic Jews as an existential threat.

In my reading of the chapter, Schaffer is not wanting to throw stones or score points but to present a rounded and reflective picture of why the issue of being Jewish and believing in Yeshua was and continues to be such an important matter. But he frames Messianic Jewish identity as an external problem for the Jewish community rather than as an authentic expression of Jewish faith. The very heart of what it means to be Jewish and British today is at stake if the thousands of Jewish disciples of Yeshua in the UK today are to be recognised and accepted by our families, communities and synagogues. In comparison to LGBTQ+ Jews, we still have a way to go.

Schaffers tour of British Jews includes the Jewish youth movements many of us grew up in, the changes due to Aliyah, assimilation and secularisation. Writing during Covid he was not able to take on board the changes we have witnessed in increased conversions to Judaism, changes in patterns of synagogue membership and increased attendance (online) and some of course the cataclysmic effects of the Israel-Gaza war, the topic that will dominate our lives and thoughts in the years to come. Schaffers conclusion “Ending, Shmending” ends by reflecting on the ongoing development of British Jewish identity and the community’s resilience and adaptability. What more could you want from a history book?

Schaffer is to be congratulated for making a significant and brave contribution to understanding the multifaceted nature of British Jewry, offering fresh perspectives on identity, inclusion, and the community’s future. What does it really mean to be Jewish today?

Prayer and Reflection:

Becoming a disciple of Yeshua in the 1970s, I experienced personally much of the story Schaffer tells, not just because of my faith in Yeshua, but being a baby-boomer living through the 1967 Six Day War, the challenges of assimilation and antisemitism, the diversity of the UK Jewish community and the choices my friends and family were making in their construction of Jewish identity. The diversity that Schaffer describes from the margins is becoming mainstream, at least in some areas. But we have a way to go, and Jewish disciples of Jesus are part of the problem and part of the solution.

Our Father in Heaven, we thank you for the long running history of Jewish people in the UK, and for the way you have preserved us over the centuries. May we continue to be witnesses to your presence, faithfulness and love for Israel and all nations, and may we who accept Yeshua as Messiah live lives that call to mind your own sacrificial love, holiness and grace. In Yeshua the Messiah’s name we pray. Amen.

אָבִינוּ שֶׁבַּשָּׁמַיִם, אָנוּ מוֹדִים לְךָ עַל הַהִיסְטוֹרִיָּה הָאֲרוּכָּה שֶׁל הָעַם הַיְּהוּדִי בְּבְרִיטַנְיָה, וְעַל דֶּרֶךְ שֶׁבָּהּ שָׁמַרְתָּ אוֹתָנוּ לְדוֹר דּוֹר. יְהִי רָצוֹן שֶׁנּוּכַל לְהִימָּשֵׁךְ לִהְיוֹת עֵדִים לְנוֹכְחוּתְךָ, לַנֶּאֱמָנוּת וּלְאַהֲבָתְךָ לְיִשְׂרָאֵל וּלְכָל הַגּוֹיִם, וְשֶׁאָנוּ, הַמְּקַבְּלִים אֶת יֵשׁוּעַ כַּמָּשִׁיחַ, נִחְיֶה חַיִּים שֶׁמַּזְכִּירִים אֶת אַהֲבָתְךָ הַמּוֹסֶרֶת נֶפֶשׁ, קְדֻשָּׁתְךָ וְחַסְדֶּךָ. בְּשֵׁם יֵשׁוּעַ הַמָּשִׁיחַ אָנוּ מִתְפַּלְּלִים. אָמֵן.

Avinu Shebashamayim, anu modim lekha al hahistoria haaruka shel ha’am hayehudi beBritanya, ve’al derekh shebah shamarta otanu ledor dor. Yehi ratzon shenukhal lehimashekh lihyot edim lenokhukhutekha, lane’emanut ule’ahavatkha leYisrael ulekhol haggoyim, veshe’anu, hamekabbelim et Yeshua kamashiach, nihye chayim shemazkirim et ahavatkha hamoseret nefesh, kedushatkha vechasdekha. Beshem Yeshua Hamashiach anu mitpallelim. Amen.

Gavin Schaffer. 2025. An Unorthodox History, Manchester University Press. Price £20

I hope that this excellent work acts as a catalyst in promoting the ongoing dialogue in these areas. Take a moment to appreciate the quality and framing of the questions. I would expect nothing less from you, Richard.

LikeLike