The International Theological Commission’s document, “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour: The 1700th Anniversary of the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (325-2025),” commemorates the pivotal role of the Nicene Creed in articulating the Christian faith. From a post-supersessionist Messianic Jewish perspective, several aspects of this document warrant both appreciation and critique.

This is a very substantial document (nearly 4,000 words) worthy of careful study, for all who have an interest in Jewish-Christian relations and Messianic Judaism. Whilst the original Council in 325 met without input from Jewish bishops, the present document included as one of its contributors Bishop Etienne Veto, a Jewish disciple of Yeshua and member of Yachad BeYeshua. The document re-affirms the ongoing election and God’s unbroken covenant with Israel, mentioning new developments in Christology from postsupersessionist and Jewish scholars like Daniel Boyarin, referring to the Jewish humanity of Yeshua and the ongoing calling of the Jewish people. It does not specifically mention the place of Jewish disciples of Yeshua within the whole body of Messiah, but breathes a spirit of generous welcome to all. It is particularly refreshing to see such a document in these times.

Some observations on the document

- Emphasis on the Trinity and Incarnation: The document underscores the Nicene Creed’s proclamation of a God who is Love and Trinity, and who, out of love, becomes one of us in His Son. This focus aligns with Messianic Jewish beliefs that recognize the profound mystery of God’s nature and His intimate relationship with humanity.

- Call for Unity: Highlighting the Creed’s role in fostering unity among diverse Christian traditions, the document reflects a commitment to overcoming historical divisions. Messianic Jews, who often find themselves bridging Jewish and Christian communities, may resonate with efforts aimed at healing rifts and promoting mutual understanding.

- Historical Context and Supersessionism: The Council of Nicaea, convened in 325 CE, played a significant role in shaping Christian orthodoxy. However, some of its decisions have been viewed through a supersessionist lens, suggesting that the Church replaced Israel in God’s plan. For instance, the Council’s decision to separate the celebration of Easter from Passover has been interpreted as an attempt to establish a distinct Christian identity, distancing itself from its Jewish roots. This perspective can be troubling for Messianic Jews who uphold the ongoing covenantal relationship between God and the Jewish people. Paragraph 46 of the document significantly challenges these wrong understandings and seeks to distance itself from anti-Judaism:

46. Let us note that it is in the context of the Council of Nicaea that the Church decisively chooses to separate itself from the date of the Jewish Passover. The argument that the Council wanted to distance itself from Judaism has been advanced on the basis of the letters of the Emperor Constantine reported by Eusebius, which present in particular anti-Jewish justifications for the choice of a date of Easter that was not linked to the 14th of Nissan. [62] However, it is necessary to distinguish the motivations attributed to the Emperor from those of the Fathers of the Council. In any case, nothing in the canons of the Council expresses such a rejection of the Jewish way of doing things. One cannot ignore the importance for the Church of the unity of the calendar and of the choice of Sunday to express faith in the resurrection. Today, at a time when the Church is celebrating the 1700th anniversary of Nicaea, these remain the aims of a reflection on the date of Easter. Beyond the calendar issue, it would be desirable to increasingly emphasize the relationship between Easter and Pesaḥ , both in theology and in homilies as well as in catechesis, in order to achieve a broader and deeper understanding of the meaning of Easter.

4. Exclusion of Jewish Voices: The Nicene Creed was formulated without the participation of Jewish believers in Jesus, leading to a formulation of faith that does not fully encompass the Jewish context of Jesus’ life and mission. This exclusion can be seen as a missed opportunity for a more inclusive and representative expression of the faith that acknowledges the Jewishness of Jesus and the early followers. The document emphasises the full Jewish humanity of Yeshua, recognises the original Council did not cover this in detail, and that “this silence in no way signifies the transience of the election of the people of the Old Covenant.“

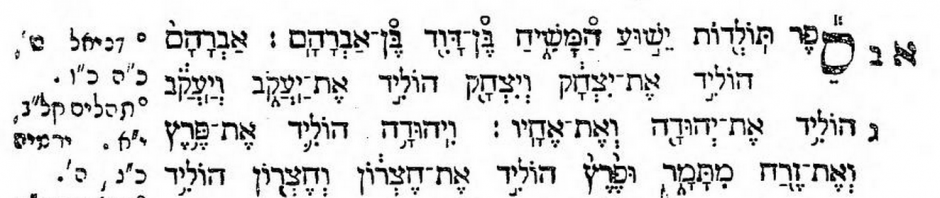

26. Despite its insistence on history, the Creed does not explicitly mention or evoke a large part of the content of the Old Testament, in particular the election and history of Israel. Obviously, a Creed does not have to be exhaustive. Nevertheless, it is useful to underline that this silence in no way signifies the transience of the election of the people of the Old Covenant. [38] What the Hebrew Bible reveals is not only a preparation but is already the history of salvation, which will continue and be fulfilled in Christ: “The Church of Christ recognizes that the beginnings ( initia ) of her faith and her election are already found, according to the divine mystery of salvation, in the Patriarchs, in Moses and in the Prophets.” [39] The God of Jesus Christ is the “God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob”, he is the “God of Israel”. Moreover, the Creed discreetly emphasizes the continuity between the people of Israel and the people of the new covenant through the mention of the “Virgin Mary,” which places the Messiah in the context of a Jewish family and a Jewish genealogy and which also echoes an Old Testament text ( Is 7:14 LXX). This creates a bridge between the promises of the Old Testament and the New, as will the expression “he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures” in the following article, where “Scriptures” means the Old Testament (cf. 1 Cor 15:4). The continuity between the Old and New Testaments is encountered again where the article on the Spirit indicates that he “spoke through the prophets,” which is perhaps an anti-Marcionite note. [40] In any case, to be fully understood, this Symbol born of the liturgy takes on all its meaning when it is proclaimed in the liturgy and articulated with the reading of the whole of the Sacred Scriptures, the Old Testament and the New Testament. This places the Christian faith in the framework of the economy of salvation which includes in an original and structural way the chosen people and their history.

5. Potential Marginalization of Jewish Identity: While the document celebrates the universality of the Nicene Creed, there’s a risk that this emphasis might overshadow the unique identity and calling of the Jewish people within God’s redemptive plan. A post-supersessionist approach advocates for recognizing and valuing the distinctiveness of Jewish identity and its ongoing significance, rather than subsuming it entirely under a broader Christian framework. The document mentions Israel and the Jewish people some twenty-five times, including:

84. Revelation, which establishes communion between God and the human being, needs recipients who have their own consistency if they are to be able to receive it in full freedom and responsibility. Hence the election of the people of the twelve tribes of Israel, who had to distinguish themselves from all other peoples and laboriously learn to separate, first on their own, truth from error. Hence Jesus Christ, in whom the Son of God truly becomes man, a Jew, a Galilean, whose humanity bears the cultural signs of the historical journey of his people. Hence the Church, constituted from all nations. Thus, relying on the Thomasian principle according to which “grace presupposes nature”, and expanding on it, Pope Francis adds: “Grace presupposes culture and the gift of God is incarnated in the culture of those who receive it”. [138]

Reflection:

The International Theological Commission’s document offers valuable insights into the theological legacy of the Nicene Creed and its role in shaping Christian faith and unity. From a post-supersessionist Messianic Jewish viewpoint, it’s essential to engage critically with this legacy, acknowledging both the profound aspects of the Creed and the historical contexts that may have marginalized Jewish perspectives. Such engagement encourages a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of faith that honors the contributions and identities of all believers.

Here is a prayer of thanksgiving and praise inspired by the International Theological Commission’s document, “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour: The 1700th Anniversary of the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (325–2025),” offered from a post-supersessionist Messianic Jewish perspective. The prayer is given in English, Hebrew with vowels, and transliteration.

Prayer of Thanksgiving, Unity, and Reconciliation

English

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who has revealed Yourself in Yeshua the Messiah—Son of God, Son of Man, true light from true light, begotten not made, of one essence with the Father.

We thank You for the faith proclaimed at Nicaea, for the gift of the Spirit who speaks through the prophets, and for the unity of the Church throughout the ages. We bless You for this document, which acknowledges the enduring election of Israel and honors the Jewish humanity of Yeshua.

May the truths confessed in the Creed lead to deeper unity among all who call upon the name of Yeshua—Jew and Gentile, one in Messiah. Heal the wounds of division. Remove every root of pride, supersessionism, and exclusion. Let the Church remember her Jewish roots, and let Israel behold her Messiah.

Bring peace to Jerusalem, reconciliation to Your people, and love among the family of faith. May the day hasten when all nations will worship You together in spirit and in truth, under the banner of the Lamb who was slain and lives forever.

Amen.

Hebrew

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, שֶׁנִּגְלָה בְּיֵשׁוּעַ הַמָּשִׁיחַ – בֵּן הָאֱלֹהִים, בֶּן אָדָם, אוֹר אֱמֶת מֵאוֹר אֱמֶת, נוֹלַד וְלֹא נִבְרָא, שֶׁהוּא בְּמַהוּתוֹ אֶחָד עִם הָאָב.

אוֹדִים אֲנַחְנוּ לְךָ עַל הָאֱמוּנָה שֶׁנֶּאֱמְרָה בְּנִיקְיָה, עַל מַתְּנַת הָרוּחַ שֶׁדִּבֵּר עַל יְדֵי הַנְּבִיאִים, וְעַל אַחְדוּת הַכְּנֵסִיָּה בְּכָל הַדּוֹרוֹת. מְבֹרָךְ אַתָּה עַל הַמִּסְמָךְ הַזֶּה, הַמַּכִּיר בִּבְחִירַת יִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁאֵינָה נִפְסֶקֶת וּמְכַבֵּד אֶת הַיְּהוּדִיּוּת שֶׁל יֵשׁוּעַ.

יְהִי רָצוֹן שֶׁהָאֱמֶת שֶׁבַּסִּימְבּוֹלוֹן תָּבִיא לְאַחְדוּת עֲמוּקָה בֵּין כָּל הַמַּאֲמִינִים בְּשֵׁם יֵשׁוּעַ – יְהוּדִים וְגוֹיִים, אֶחָד בַּמָּשִׁיחַ. רְפָא נַע סֶדֶק וּמַחֲלוֹקֶת. הָסֵר כָּל גַּאֲוָה וְהַחְלָפָה וְהַפְלָיָה. תַּזְכֵּר אֶת הַכְּנֵסִיָּה בְּשָׁרָשֶׁיהָ הַיְּהוּדִיִּים, וְתַגְלֶה אֶת הַמָּשִׁיחַ לְיִשְׂרָאֵל.

הָבֵא שָׁלוֹם לִירוּשָׁלַיִם, פִּיּוּס לְעַמְּךָ, וְאַהֲבָה בֵּין כָּל בְּנֵי הָאֱמוּנָה. יָבֹא מְהֵרָה הַיּוֹם אֲשֶׁר בּוֹ יַעַבְדוּךָ כָּל הָעַמִּים בְּרוּחַ וֶאֱמֶת, תַּחַת נֵס הַשֶּׂה שֶׁנִּשְׁחַט וְחוֹזֵר לִחְיוֹת לָנֶצַח.

אָמֵן.

Transliteration

Barukh Atah Adonai Eloheinu Melekh ha-olam,

she-niglah b’Yeshua ha-Mashiach – Ben haElohim, ben adam,

or emet me’or emet, nolad v’lo nivra,

she-hu b’mahuto echad im haAv.

Odim anachnu lekha al ha-emunah she-ne’emrah b’Nikyah,

al matnat haRuach she-diber al yedei ha-nevi’im,

v’al achdut haKnesiyah b’khol ha-dorot.

Mevorakh Atah al ha-mismakh ha-zeh,

ha-makir bivchirat Yisrael she-einah nifseket

u-mechabed et ha-yehudiyut shel Yeshua.

Yehi ratzon she-ha-emet she-ba-Simbolon

tavi le-achdut amukah bein kol ha-ma’aminim

b’Shem Yeshua – Yehudim ve-Goyim, echad baMashiach.

Refa na sedeq u-machaloket.

Haser kol ga’avah, hachlafah, ve-haflayah.

Tazker et haKnesiyah b’shorasheha ha-yehudiyim,

ve-tagleh et haMashiach le-Yisrael.

Havei shalom liYerushalayim, piyus le-amkha,

ve-ahavah bein kol bnei ha-emunah.

Yavo meheira ha-yom asher bo ya’avdukha

kol ha-amim b’ruach ve-emet,

tachat nes haSeh she-nishchat ve-chozer lichyot lanetzach.

Amen.

For a deeper exploration of the Council of Nicaea’s impact, you might find this video informative: