14 August 1888 Nathanael Kameras declares his faith in Yeshua #otdimjh

Kameras, Rev. Nathanael, missionary in Vienna, of the British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel among the Jews. The following is an abridged extract from his autobiography [Bernstein: Some Jewish Witnesses]:—

“On the road leading from Russian Lithuania to [303] Russian Poland there stands a large and lonely inn. It was there that I first saw the light of day in the year 1862. A clay-floored entrance divides the rooms of this extensive house into two rows; on one side are the rooms for the strangers, who lodge here over night, the large tap-room, and the small rooms belonging to my parents; on the other, a one-windowed chamber, where our teacher slept, and the hall, a pretty large room, set apart for prayer and study. It contained long narrow tables and forms, an ornamented cupboard on the eastern side, in which the Thora-rollen (law scrolls) were kept, a prayer-desk with a seven-branched brass candelabra and a hanging lamp. The male members of our family, and Jews from the neighbouring villages, assembled there for Divine Service, to which the women listened in an adjoining room. There, too, our teacher instructed my four brothers and myself in the Hebrew language, and in the Talmud.

As soon as I was five years of age, my parents, wrapping me up in a Tallith (prayer-mantle), solemnly brought me in there, in order that I might receive the necessary instruction; so that from that moment I devoted myself exclusively to study. Every other occupation, every other employment, every recreation, game, or fun of childhood, all that makes the heart light and the body strong, was banished from my life. I felt like a bird imprisoned in a cage, and debarred the free movement of its limbs; outside, was the world in all its beauty, where numbers of joyous creatures were flying about in the full enjoyment of their individual freedom, whilst [304] I, powerless, clung to the bars.

Before my eyes lay a landscape, rich in rural splendour; as far as I could see, village after village, surrounded by fruit-laden trees, presented a most cheerful aspect, and from the window I could watch the Christian children at their play, enjoying the fresh air of freedom in the flowering fields and sprouting meadows. Amidst the songs of birds, the rustling of leaves and the roar of the forest, I caught the sound of happy human voices, whilst I, chained to my books all day and until late at night, was forced to pore over marriage contracts and divorces and other similar things, which would have been better kept from my childish reason. ‘Oh, if I were only that poor farm-servant coming home from the fields with the tired horses, or that ragged boy driving his cows home!’ Thus I sighed. But all my longings and wishings were useless; I had to go over the same tiresome road that all the Jewish children of orthodox parents must labour through. The master behind me, drove me on with a volume in one hand and the rod in the other; my father drove me, my relations drove me, and thus, without rest or quiet, I was hurried through all those voluminous works that are of no value for practical existence whatever, so that the years of my childhood passed by, joyless and unenjoyed.

“This Jewish elementary school, called Cheder, seemed to me just like a prison, and the teacher, who bore the title of Melamed, I looked upon as a jailer, so that when the news reached me of my parents’ resolve to send me to a Yeschiva, I welcomed it with [305] the same joy with which a convict welcomes his acquittal after long and hard imprisonment.

“It was not difficult to find a suitable Talmud school for me. The son-in-law of our district Rabbi was Rosh-Yeshiva (professor at a Talmud college) in a town where an uncle of mine lived. Thither my parents sent me shortly after I had been confirmed (Bar mitzvah), that is to say, when I had completed my thirteenth year. There, in his private lodgings, I visited Rabbi Schimele Wolf, for so the Talmud lecturer was called, and begged him to accept me as a pupil. At first he received me very coldly, and with dignity that involuntarily pointed to the importance of his position, but after I had delivered the recommendations I brought from his father-in-law, and had told him that his family doctor was my uncle, the stern look in his coal-black, thoughtful eyes, that shone like two glowing specks out of his pale face, fringed by a black beard, relaxed, and with extreme friendliness, he dispensed with the usual examination on entrance, and ordered his servant to lead me to the Yeshiva, and assign me a place there. We were still at a considerable distance from our destination when a great noise of human voices broke on my ear, and when at last I entered the hall, in which the Yeshiva was held, I was quite stunned by the terrific noise that was being made there.

More than a hundred boys, youths of about thirteen to twenty years of age, were assembled, each one screaming and moving about in unrestrained restlessness. Some of them were sitting round long, narrow tables, continually swaying the [306] upper part of their bodies backwards and forwards or from side to side. Others were standing in front of small portable desks, leaning over them or swaying to and fro with them, or going round and round them. Each boy had a ponderous volume open before him, from which he chose a passage, that he quoted at the top of his voice. One roared like a lion, ‘Omar Rabbi Akiwa (Rabbi Akiwa said) sa……id, sa……id ..Ra……bbi…A……ki……wa…, oi Mamuni (Oh Mammy) Rabbi, oi Tatutim, (Oh Daddy) Akiwa, oi Ribene schel olam (Oh Lord of the World) said; said Rabbi Akiwa; what did Rabbi Akiwa say? A …ki….wa…sa……id…,’ and so on for hours. Another sang very daintily, imitating the voice of the chanter in sad and joyful melodies, such as had remained in his memory from the various festivals, or he composed something at will, with the following words; ‘According to the doctrine of Samai it is permitted to eat an egg that has been laid on a holiday on that same day, whereas according to the doctrine of Hillel, it is forbidden.’ My arrival attracted their attention and had a subduing effect; there was a lull. Suddenly a voice cried: ‘The Massgiach (overseer) is coming.’ This was uttered in the same sing-song manner, as though the boy were studying some sentence out of the Talmud.

It was repeated by a second, then a third and a fourth in the same manner, and was the signal for them all of one accord to begin their lamentations and singing afresh, with increased vigour, endeavouring to drown each other’s voices. It is in this way that these pale boys and[307] youths prepare for the ‘Schir’ (lecture), which lasts from two to four o’clock in the afternoon, taking place daily, and being carried out in the following manner:—The scholars stood round in a semi-circle at the feet of the Rabbi, who sat on an elevated chair at a desk. Charging one pupil to read a certain passage out of the Talmud, he desired another to read the commentaries to it, and again a third to read and explain the marginal notes to those commentaries.

“In the quiet cloisters of a large town I met a lonely man, living one day like another, a quiet and edifying life, to whom I felt particularly attracted. His head was a real study; a long white beard covered his breast, and he had a high, broad forehead, a finely arched nose, and large blue eyes, in which a whole world of goodness lay; over his features there was an expression of touching humility, as though he would excuse himself to everyone for daring to breathe the air and to fill a space in the universe. Hoping that with him I should not fare badly, I settled down there, and indeed, I did not regret it. From the beginning he showed me his goodwill in unlimited measure, taking care that I should receive free board from the prayer-men, who assembled there three times a day, and in such wise that I boarded with a different one each day in the week; besides which he contrived to give me ample pocket-money.

I was often allowed to substitute him in reading ‘Mischnais for anniversaries’ (extracts from the Talmud to be read for the departed souls on the respective days of their death, which the relations generally remunerate well). He took me[308] with him wherever he was called to sing psalms or say prayers, either at the cradle of a new-born child that had scarcely opened its eyes to the light, or at the bedside of the dying, closing them to the light, to a wedding-feast or to a death-watch, and everywhere money poured in. Thus we lived together day and night in a neighbourly, friendly manner in the cloisters, and nothing lay further in the recluse’s thoughts than that he should rob me of my peace of mind, which, however, he did without wishing to do so. His fervent prayers for the redemption of the people of Israel it was that had such a striking effect on my mind. Years will not efface from my memory the sight of that old man at midnight, when all around was quiet, and he thought himself unobserved, taking off his shoes and seating himself on the floor, imploring the Lord in heartfelt sincerity, in His mercy to return to Jerusalem and reign there as He had prophesied.

I still hear those heart-rending tones, in which he prayed; ‘Stretch out Thy right hand, Oh God! and in mercy redeem the people of Israel. Oh, that it might soon be announced to the unhappy nation: “Your Redeemer has come to Zion!”‘ Every sentence was accompanied by a sigh or broken by a sob. He imagined me to be asleep, but I heard every word, and was often moved to tears, involuntarily beginning myself to pray eagerly and perseveringly that the Messiah might soon come and release His people from captivity. From henceforth I devoted much thought to the subject, and, in my childish fancy, pictured to myself how glorious it would be when the Messiah would come,[309] and, as a child rejoices to greet its father from afar, I looked forward, daily and hourly, to the advent of the Redeemer of Israel. On the other hand, the question often worried me; Why does not God answer such real and fervent prayers? Why does not the Messiah come to release His people? I did not dare to speak to Rabbi Todresch, such was the name of the recluse, on the subject, but once when a Talmudist from some well-known Talmud school came back to his home in the cloisters, I told him what it was that troubled me so much, and my astonishment was indeed great when I heard his answer: ‘Prayers such as those will and can never be answered; for the Messiah has come.’

In vain did I beg him to explain it to me, but he purposely avoided all my questions, telling me only so much that he possessed a book which explained the question thoroughly, but which he could not entrust to me for fear of the consequences such a step might have for himself; besides, it would be of no use to me, as I should have to give up my present career entirely. ‘If you want to know the full truth,’ he said to me, ‘you must go abroad, for only there can you search after the truth freely and independently; whereas here, you must sell your freedom for your bread.’ Tortured by restlessness, despair and longing, and fearful lest my parents should get ear of the change in my heart, when they would certainly oppose my plans, I decided to follow his advice at once and to leave Russia.

“After taking a hearty leave of the recluse, and my new friend, the Talmud student, I seized my staff and[310] went out into the wide world, a toy for wind and weather. Like a nomad, I wandered uncertain, for a long period, from town to town and from village to village. It was quite late often when I reached a strange place; all the doors and gates were closed, and I turned my steps to the ever open house of God, entered upon a ‘Kasche’ (a Talmudic question of dispute) with any one of those present, and I immediately felt at home, had my board and lodging, and the pious prayer-men, who came there daily, openly and secretly pressed their charitable gifts into my hand. Thus I was enabled to wander through the whole of Russia to the frontier, which, having no passport, I could not legally cross, and was therefore forced to smuggle myself through by giving a man a rouble to conduct me through a wood which led into Germany. Now that I was in another country, my position became a different one. On reaching the first German town, I asked as usual for the ‘Beth-Hamedrash’ (Jewish prayer and school-house), but to my greatest dismay no one could give me any information. Only one thing I was aware of, and that was that I could not make myself understood at all. It was evening; the first stars, those companions of my wanderings, began to twinkle in the sky, but into my sad heart no light would enter; there all was dark and dull. Here I was, standing at the corner of a street leaning against a post, a little bundle in my hand, without means, work, knowledge or language; alone, forsaken, not knowing where to turn. A lady passing by stopped and looked at me inquisitively.

The sight of a [311] slender little lad, clothed in the long wide Kaftan, with a pale face and sad eyes filled with tears, must have aroused her sympathy. She addressed me, but finding I did not understand a word she said, she gave me a few pence and showed me an inn where I could pass the night. It was certainly a very cheap night’s-lodging that I had, but I was obliged to sleep amongst tipsy room-companions, to whom I was much too interesting a personage for them to leave in peace. Some would insist on making a common covering of my long coat; others played incessantly with my long fore-locks, whilst others again were interested in my Arba-Kanfoth (a garment with fringe at the ends) and were continually pulling at them. It was a long, weary night that I passed there, and as soon as the rising sun shone faintly through the dirty window-panes I hastened out, and, being once more alone, allowed my tears to flow. For the first time since my departure home-sickness with all its overwhelming power quite overcame me, and I felt the seriousness of life in its full meaning.

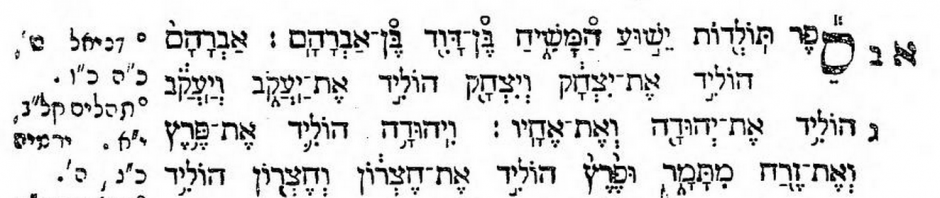

However, I soon took courage again, laid my Tephillin (prayer-strap) on and implored the Lord to lend me His assistance and protection, taking a solemn oath that from henceforth I would blindly let myself be guided by Him in all things. With this sacred oath and with the firm conviction that the Lord would carry out all to His glory, I went on my way. With great difficulty and many privations I reached Breslau, where I met a man from Russia, who assisted me in obtaining a place as instructor of the Hebrew language in a Polish [312] Jew’s family. After staying there a few months I seemed, curiously enough, to be drawn as by an invisible hand towards Vienna. The money I had earned as a teacher amply sufficed to take me there, and after a lengthy search, I found inexpensive lodgings in a Jewish family. (The head of the family is dead, but the wife still lives here, and her son is now, thanks be to God, a dear believing Protestant Christian.) Here I became acquainted with a Jewish shoemaker, who was the first to give me a New Testament in the Hebrew language to read. The very first sentence in that book was sufficient to draw me to it like a magnet, for there it was written what that Talmud-scholar had briefly told me, written clearly and in full, namely, that the Messiah, who until now had been the object of my prayers, my desires and hopes, had actually been born. On asking him to tell me something more about the book, the shoemaker conducted me to the missionary, Herr E. Weiss, who advised me to go to Pastor Schönberger, preacher at Prague, where I found a very friendly welcome. I passed the winter there, but, as Pastor Schönberger was obliged to be away for a year, he took me to his friend, the Rev. D. A. Hefter, L.J.S. missionary at Frankfort-on-the-Main, who kindly took me under his paternal care.

“The year 1881 was a decisive one for me. The Word of Life rooted itself deeper and deeper in my heart; prejudices vanished one by one, and the love of Jesus took their place. I perceived how deeply my heart had been wounded by sin; but at the same time [313] I acknowledged the most lovable of all the children of the earth, the Son of God, who has redeemed me too through the shedding of His innocent blood, and has healed all my wounds.

On the 14th of August, 1881, I was baptized by the missionary, Herr Hefter, in the ‘Dreikönigskirche’ at Frankfort-on-the-Main, receiving the names Nathanael Karl Albert. At first I learnt the art of bookbinding in Frankfort, but as the Rev. D. A. Hefter desired me to become a pupil at the missionary-house in Barmen, I complied with his desire most willingly, regarding this step as one indicated by the Lord. One year I passed in the preparatory-school of the missionary-house, and four years in the seminary itself. During these years I received abundant blessings from the Lord. I was led deeper and deeper into the Spirit of the Word of God, and guided to more independent search by teachers endowed with truly divine minds, and treated with the greatest affection by a friendly circle of brethren, among whom I was permitted, thanks be to God, to grow stronger in faith, more fervent in love, and riper in understanding.

To serve the Lord in His empire, and to win souls for Him out of His ancient people of the covenant, was my most coveted desire, and this too the Lord has granted me in His endless goodness and mercy. At the end of the year 1887 I passed my final examinations, and at the beginning of 1888, in answer to the proposal of the British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel among the Jews, I was permitted to begin my active duty among Israel in Vienna. Three years later, in [314] 1891, I received my ordination from the celebrated theologian of Würtemberg, Dr. Burk, in Stuttgart.

“One incontestible certainty has been proved to me both in the wonderful guidance of my life as also in my profession, which I now hold for more than sixteen years, that of myself I can do nothing, not even the slightest thing, and imbued with the conviction of my powerlessness and utter helplessness, of my own poverty and wretchedness, I have learnt to make use of the sweetest privilege of our life, namely, the subjection of my own will to the will of my Saviour, Jesus Christ.”

Prayer: This story of Nathaniel Kameras challenges us today – his genuineness of spirit, the deep orthodox background in which he grew up, and his firm faith in Yeshua. Thank you, Lord, for his witness and service. In Yeshua’s name we pray. Amen.

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

LikeLike