Today we consider two of the sons of Pinkus Kaufmann Levi, who changed his name to Lehrs;

Karl Ludwig Lehrs (January 14, 1802 – June 9, 1878), was a German classical scholar.

Bernstein gives a short note:

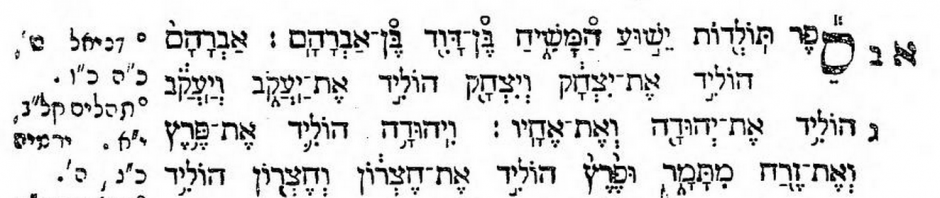

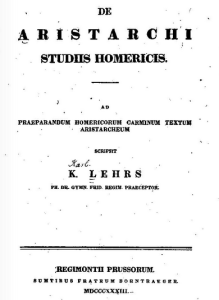

Lehrs, Karl, was born in Königsberg in 1802, and died 1878. It is recorded that while studying in Berlin he became a Christian from conviction, and was baptized [331] in 1822. A number of his relatives were influenced by him for Christianity. He was a classical teacher in several schools, and then Professor at the University of Königsberg. He published a book of considerable merit under the title, “De Aristarchi Studiis Homericis,” 1833; “Questiones Epicae,” 1837; “Pindars-scholien,” 1873

Karl Lehrs had a distinguished career as a Classical Scholar pioneering modern critical study of the works of Homer. The Jewish Encyclopedia gives more details:

German philologist; born at Königsberg, East Prussia, Jan. 2, 1802; died there June 9, 1878; brother of the philologist Franz Siegfried Lehrs (1806-43), editor of Didot’s edition of the Greek epic poets. Karl was educated at the Königsberg gymnasium and university (Ph.D. 1823); in 1822, after entering the Protestant Church, he passed the examination for teacher in the gymnasium.

He was successively appointed to positions at Danzig, Marien werder, and Königsberg (1825). In 1831 he established himself as privat-docent at Königsberg University, and in 1835 was appointed assistant professor. Elected in 1845 professor of ancient Greek philology, he resigned his position as teacher at the gymnasium; he held the chair in Greek philology until his death. Among Lehrs’s many works may be mentioned: “De Aristarchi Studiis Homericis,” Königsberg, 1833 (3d ed., by Ludwich, Leipsic, 1882); “Quæstiones Epicæ,” ib. 1837; “Herodiani Scripta Tria Minora,” ib. 1848; “Populäre Aufsätze aus dem Alterthume,” ib. 1856 (2d ed., 1875); “Horatius Flaccus,” ib. 1869; “Die Pindarscholien,” ib. 1873.

What neither Bernstein nor the Jewish Enclyclopedia tell us is that Franz Siegfried Lehrs (who continued to be known as ‘Samuel”) was a significant friend, influence and supporter of a poor young opera composer trying to make his way in Paris at the time – whose name was Richard Wagner. It was Samuel Lehrs who introduced Wagner to philosophy, gave him material from Medieval Literature which became the basis for his operas Tannhäuserand Lohengrin, and would be one of Wagner’s most significant friendships

Wagner in the circle of have-nots in the New Year’s Eve, 1841 in Paris, with the librarian Gottfried Engelbert contrast, the philologist Samuel Lehr, the painter Friedrich Pecht with his wife, and the painter Ernst B. Kietz, who portrayed the circle.

Milton Brener, an expert on Wagner’s relationships with Jewish people and his views on Judaism, writes:

We might begin with one young Jewish man named Samuel Lehrs, a struggling philologist. Lehrs was one of three of Wagner’s close friends during the composer’s two year sojourn in Paris as a young man, beginning almost ten years before his infamous essay. He, like his three friends was battling for recognition and even for basic survival. Wagner, hopelessly in debt, and earning next to nothing, was helped by the labors of his wife Minna. But his empathy for his very sickly friend, Lehrs, was boundless. In April 1842, Wagner and his wife left Paris for Dresden, but his concern for his friends centered most on Lehrs, whom he felt he would not see again. In his autobiography, written about 30 years later, in his mid-50s, he credited Lehrs with his own introduction to and absorption with philosophy, and in large part with his interest in medieval poetry. It was also Lehrs who had furnished him with source material for two of his early operas.

He continued to correspond haltingly with Lehrs, and with his other Paris friends, to whom he eagerly sought news about Lehrs and his condition, chiding them when they sent what he felt to be insufficient information. He ended one of his letters with “I don’t want to know anything about you, only about Lehrs.” He finally heard again from Lehrs directly about a year after leaving Paris. Wagner responded “Be of good courage, my dear brother. Sooner or later we must be together again… enjoy the beautiful spring air which will bring you strength.” Lehrs died a few days after receiving the letter, and Wagner wrote his younger sister that the news left him dumb, speechless for almost 8 days. It was “heartbreaking… This brave wonderful and so unfortunate man will to me be eternally unforgettable.” In his autobiography, begun at age 55, he said his relationship with Lehrs “was one of the most beautiful relationships of my life.”

Wagner’s autobiography mentions Samuel Lehrs 30 times, and records discussions with him on life after death, where Samuel seems to have less than a biblical certainty on the resurrection. Whilst Wagner recognises the worthy character of Lehrs, he reports his annihilationist view of life after death:

I had been astonished at times to hear even the grave and virtuous Lehrs, openly and quite as a matter of course, give expression to grave doubts concerning our individual survival after death. He declared that in many great men this doubt, even though only tacitly held, had been the real incitement to noble deeds. The natural result of such a belief speedily dawned on me without, however, causing me any serious alarm. On the contrary, I found a fascinating stimulus in the fact that boundless regions of meditation and knowledge were thereby opened up which hitherto I had merely skimmed in light-hearted levity.

This is not the place to examine Wagner’s anti-Semitism, which we will explore on another occasion. Here we should note the presence of a Jewish believer in Yeshua in his life and development, one whose influence was significant, despite some of his non-orthodox beliefs. From the perspective of history the younger brother, Samuel, may have left a more lasting influence on Jewish-Christian relations through his friendship with Wagner than the important works of his better known brother on the poetry of Homer.

Prayer: Lord, only you know the part we play in the history of your Church and Israel, and in wider society. We cannot discern our place, nor do we need to. Help us be faithful to your Incarnate Word, our Messiah Yeshua, and be an influence for good, wherever you place us, and whatever you give us to do this day. In Yeshua’s name we pray. Amen,

Sources and additional material:

https://allegoriesofthering.wordpress.com/how-jews-saved-the-ring/

http://miltonbrener.hubpages.com/hub/Richard-Wagner-Jewish-Friends

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5197 vol 1 wagner my life

From Richard Wagner’s autobiography

To assist us in these discussions Anders called in his friend and housemate Lehrs, a philologist, my acquaintance with whom was soon to develop into one of the most beautiful friendships of my life. Lehrs was the younger brother of a famous scholar at Konigsberg. He had left there to come to Paris some years before, with the object of gaining an independent position by his philological work.

————

What this meant in Paris I learned just about this time from the hapless fate of the worthy Lehrs. Driven by need such as I myself had had to surmount a year before at about the same time, he had been compelled on a broiling hot day in the previous summer to scour the various quarters of the city breathlessly, to get grace for bills he had accepted, and which had fallen due. He foolishly took an iced drink, which he hoped would refresh him in his distressing condition, but it immediately made him lose his voice, and from that day he was the victim of a hoarseness which with terrific rapidity ripened the seeds of consumption, doubtless latent in him, and developed that incurable disease. For months he had been growing weaker and weaker, filling us at last with the gloomiest anxiety: he alone believed the supposed chill would be cured, if he could heat his room better for a time. One day I sought him out in his lodging, where I found him in the icy-cold room, huddled up at his writing-table, and complaining of the difficulty of his work for Didot, which was all the more distressing as his employer was pressing him for advances he had made.

He declared that if he had not had the consolation in those doleful hours of knowing that I had, at any rate, got my Dutchman finished, and that a prospect of success was thus opened to the little circle of friends, his misery would have been hard indeed to bear. Despite my own great trouble, I begged him to share our fire and work in my room. He smiled at my courage in trying to help others, especially as my quarters offered barely space enough for myself and my wife. However, one evening he came to us and silently showed me a letter he had received from Villemain, the Minister of Education at that time, in which the latter expressed in the warmest terms his great regret at having only just learned that so distinguished a scholar, whose able and extensive collaboration in Didot’s issue of the Greek classics had made him participator in a work that was the glory of the nation, should be in such bad health and straitened circumstances. Unfortunately, the amount of public money which he had at his disposal at that moment for subsidising literature only allowed of his offering him the sum of five hundred francs, which he enclosed with apologies, asking him to accept it as a recognition of his merits on the part of the French Government, and adding that it was his intention to give earnest consideration as to how he might materially improve his position.

This filled us with the utmost thankfulness on poor Lehrs’ account, and we looked on the incident almost as a miracle. We could not help assuming, however, that M. Villemain had been influenced by Didot, who had been prompted by his own guilty conscience for his despicable exploitation of Lehrs, and by the prospect of thus relieving himself of the responsibility of helping him. At the same time, from similar cases within our knowledge, which were fully confirmed by my own subsequent experience, we were driven to the conclusion that such prompt and considerate sympathy on the part of a minister would have been impossible in Germany. Lehrs would now have a fire to work by, but alas! our fears as to his declining health could not be allayed. When we left Paris in the following spring, it was the certainty that we should never see our dear friend again that made our parting so painful.

My intercourse with Lehrs had, on the whole, given a decided spur to my former tendency to grapple seriously with my subjects, a tendency which had been counteracted by closer contact with the theatre. This desire now furnished a basis for closer study of philosophical questions. I had been astonished at times to hear even the grave and virtuous Lehrs, openly and quite as a matter of course, give expression to grave doubts concerning our individual survival after death. He declared that in many great men this doubt, even though only tacitly held, had been the real incitement to noble deeds. The natural result of such a belief speedily dawned on me without, however, causing me any serious alarm. On the contrary, I found a fascinating stimulus in the fact that boundless regions of meditation and knowledge were thereby opened up which hitherto I had merely skimmed in light-hearted levity.

In my renewed attempts to study the Greek classics in the original, I received no encouragement from Lehrs. He dissuaded me from doing so with the well-meant consolation, that as I could only be born once, and that with music in me, I should learn to understand this branch of knowledge without the help of grammar or lexicon; whereas if Greek were to be studied with real enjoyment, it was no joke, and would not suffer being relegated to a secondary place.

https://allegoriesofthering.wordpress.com/how-jews-saved-the-ring/

Samuel Lehrs

Wagner considered himself a philosopher first and a composer second. The man who sparked his interest in philosophy was Samuel Lehrs, an indigent Jewish philosopher whose life and early death are reminiscent of a Puccini character out of La Boheme. Lehrs was instrumental in helping Wagner find inspiration for his operas Tannhauser and Lohengrin. Years later, upon learning of Lehrs’ death Wagner was so devastated that he could not speak for over a week. He said his relationship with Lehrs was one of the most beautiful of his life.

Some critics accuse Wagner of saying this so that he wouldn’t appear to be anti-Semitic, but the facts speak otherwise. Wagner had an important, meaningful connection with Lehrs, as he did with many other Jewish artists who helped him when Wagner was putting together The Ring and Parsifal.

http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/5144/pg5144.html wagner – my life vol 2

For a long time I had wanted to understand the real value of philosophy. My conversations with Lehrs in Paris in my very young days had awakened my longing for this branch of knowledge, upon which I had first launched when I attended the lectures of several Leipzig professors and in later years by reading Schelling and Hegel.

Levi, Pinkus

Namensvarianten

Lehrs, Pinkus (seit 1812); Levi, Pinkus Kaufmann

Lebensdaten

1760 bis 1833

siB

-Wag

Wagner in the circle of have-nots in the New Year’s Eve, 1841 in Paris, with the librarian Gottfried Engelbert contrast, the philologist Samuel Lehr, the painter Friedrich Pecht with his wife, and the painter

Ernst B. Kietz, who portrayed the circle.

Classical scholar, Hellenist

* 1806 Königsberg / † 13 April 1843, Paris

Lehr was born as the son of manufactured goods merchant Levi Pinkus merchant in Königsberg. Since 1812, the family took the surname Lehrs. At his baptism Lehrs adopted the name Franz Siegfried, among friends he called himself, however, continue to Samuel. Lehr studied like his older brother Karl Ludwig Lehrs classical philology at the University of Königsberg. While Karl Ludwig Lehrs after his conversion to Christianity finally received a full professorship in Königsberg and as one of the most important classical scholars of his time was, Samuel Lehr had to give up his studies because of health problems. After a short time as a private tutor, he worked as a freelance scholar in Paris and earned his living as an editor and translator of ancient Greek authors for the publisher Didot.

Samuel Lehr was, together with the painter Ernst B. Kietz of the closest friends of Richard Wagner in Paris1839-1842. Wagner was encouraged by Lehrs to deal with the Middle High German poetry. In a band of Historical and literary papers of the University of Königsberg, which he had received from Lehr Wagner first read the epic of “Sängerkrieg” in the original text and a summary of the “Lohngrin” seal.

From DresdenWagner wrote in 1842 to the left in Paris Lehrs that he had returned not from patriotism to his home: “I have set aside no preference geographically and my country, its beautiful hills, valleys and forests, I even contrary. This is a cursed people, this Saxony – greasy, dehnig, clumsy, lazy and rude – what have I to do with them? ”

Wagner He has no one among his friends tenderly loved as the Parisian misery Comrade Samuel Lehrs and virtuoso pianist Carl Tausig.

Lehrs died in 1843 in Paris at the consequences of tuberculosis.

Lehrs anb Wagner were friends. Rubinstein and Hermann Levi, too. Wagner had a lot of friends Jews. Theodor Herlz was very Wagnerian and the first Sionist. He loved Tannhäuser. Tannhäuser’s overture sounded in Basil in the 2nd Sionist Congress.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mind is blown. I didn’t know Wagner, with all his anti-semitism, had any Jewish friends.

LikeLike

He had many – including those who conducted and promoted his work!

LikeLiked by 1 person